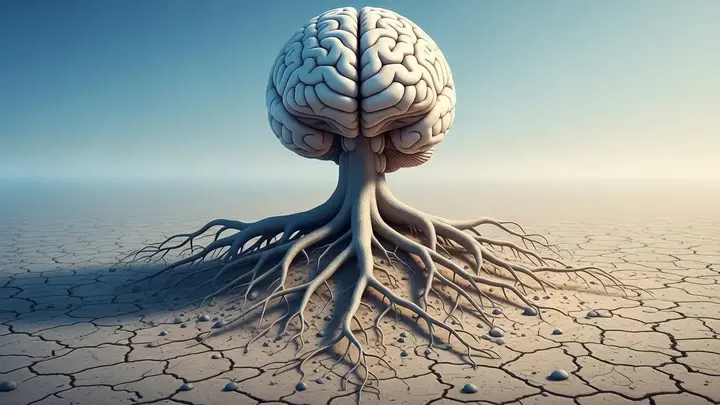

The psychology of resilience refers to the mental and emotional processes that enable individuals to adapt effectively to adversity, stress, trauma, and significant life challenges.

Resilience is not a fixed personality trait; it is a dynamic psychological capacity shaped by cognition, emotion regulation, behavior, and social context.

We recognize resilience as the ability to maintain or regain psychological well-being in the face of disruption, while continuing to function, grow, and pursue meaning.

At its core, resilience reflects how the mind interprets difficulty, mobilizes internal resources, and transforms hardship into adaptive learning.

This psychological flexibility allows individuals to withstand pressure without losing their sense of purpose or identity.

Table of Contents

Cognitive Foundations of Psychological Resilience

Cognition plays a central role in resilience. The way individuals think about stressors determines whether those stressors overwhelm or strengthen them.

Cognitive appraisal, the mental evaluation of events, directly influences emotional and behavioral responses. Resilient individuals tend to interpret challenges as manageable, temporary, and meaningful rather than permanent or catastrophic.

Key cognitive elements include:

- Adaptive belief systems that support optimism grounded in realism

- Growth-oriented thinking, viewing setbacks as opportunities for learning

- Self-efficacy, the belief in one’s ability to influence outcomes

These mental frameworks reduce perceived threat and enhance problem-solving capacity. The psychology of resilience is therefore deeply tied to how meaning is constructed under pressure.

Emotional Regulation and Resilience

Emotional regulation is a defining component of resilient functioning. The ability to experience intense emotions without being controlled by them allows individuals to respond deliberately rather than react impulsively. Resilient minds do not suppress emotions; they integrate them.

Effective emotional regulation involves:

- Awareness and acceptance of emotional states

- Modulation of emotional intensity through cognitive strategies

- Recovery after emotional disruption

This emotional agility prevents prolonged stress activation and protects mental health. In the psychology of resilience, emotional balance supports clarity, endurance, and sustained motivation.

Neuropsychology of Resilience

Resilience is also grounded in brain function. Neuropsychological research highlights the interaction between the prefrontal cortex, responsible for executive control, and the amygdala, which processes threat and fear.

Resilient individuals demonstrate stronger prefrontal regulation over emotional reactivity, enabling calmer responses under stress.

Neuroplasticity further explains resilience as an adaptive process. The brain rewires itself in response to experience, strengthening neural pathways associated with coping, learning, and emotional regulation. Over time, repeated adaptive responses reinforce resilient patterns, making resilience increasingly accessible.

Personality Traits That Support Resilience

Certain personality characteristics consistently align with higher resilience. These traits do not eliminate stress but enhance adaptive response capacity.

Prominent resilience-supporting traits include:

- Psychological hardiness, marked by commitment, control, and challenge orientation

- Conscientiousness, supporting discipline and persistence

- Emotional stability, reducing vulnerability to overwhelm

We understand these traits not as determinants but as facilitators that interact with experience and environment to shape resilient outcomes.

The Role of Meaning and Purpose

Meaning-making is a powerful driver in the psychology of resilience. Individuals who can connect adversity to a broader sense of purpose demonstrate stronger endurance and recovery. Purpose transforms suffering into significance, reducing feelings of helplessness.

A strong sense of meaning:

- Anchors identity during disruption

- Guides decision-making under uncertainty

- Sustains motivation during prolonged difficulty

Resilience flourishes when experiences, even painful ones, are integrated into a coherent life narrative that affirms values and direction.

Social and Relational Dimensions of Resilience

Resilience is not solely an internal process. Social connection profoundly influences psychological resilience. Supportive relationships provide validation, perspective, and emotional safety, buffering the impact of stress.

Key relational contributors include:

- Secure attachment and trust

- Emotional responsiveness from others

- Shared problem-solving and encouragement

Social environments shape how individuals perceive threat and access coping resources. The psychology of resilience recognizes interpersonal connection as a critical stabilizing force.

Resilience Across the Lifespan

Resilience manifests differently across developmental stages. During childhood, it is shaped by caregiving quality, emotional modeling, and early coping experiences.

As individuals mature, resilience reflects accumulated skills, identity stability, and role flexibility, while later life emphasizes acceptance, wisdom, and emotional prioritization.

Across the lifespan, resilience evolves through:

- Experience-based learning

- Refinement of coping strategies

- Shifts in values and goals

This developmental perspective emphasizes resilience as a lifelong adaptive capacity rather than a static attribute.

Stress, Trauma, and Post-Adversity Growth

Exposure to stress and trauma does not preclude resilience. In many cases, adversity catalyzes post-adversity growth, a phenomenon where individuals report increased strength, insight, and appreciation for life following hardship.

Psychologically resilient individuals often experience:

- Enhanced self-understanding

- Deeper relational connections

- Strengthened values and priorities

This growth does not negate pain; it reflects the mind’s ability to reorganize meaning and identity after disruption.

Building Psychological Resilience Through Practice

Resilience can be intentionally cultivated. Psychological research identifies practices that strengthen resilience by reinforcing adaptive cognitive, emotional, and behavioral patterns.

Effective resilience-building practices include:

- Structured reflection and self-awareness

- Cognitive reframing to challenge limiting beliefs

- Consistent engagement in purposeful activities

- Development of emotional regulation skills

Through deliberate practice, individuals enhance their capacity to navigate complexity, uncertainty, and change.

The Psychology of Resilience in Modern Life

In an era characterized by rapid change, uncertainty, and pressure, the psychology of resilience is increasingly vital.

Resilience supports not only survival but sustained performance, creativity, and psychological well-being. It enables individuals to remain functional without becoming rigid, adaptive without losing integrity.

We view resilience as the mental architecture that allows the human mind to absorb shock, reorganize, and continue forward with clarity and strength. It is the psychological foundation of endurance, transformation, and long-term flourishing.